On his second album, “Watching Movies With the Sound Off”(Rostrum), he’s threatening to become a great rapper himself, a startling turn of events. Miller himself remained something of a cipher, long on charm but short on memorable lyrics, even though he was clearly influenced by and given to mimicking great rappers like Big L. It demonstrated that there were several ways to get to the finish line first.īut Mr. Miller’s success was perhaps the most definitive proof to a slumbering hip-hop industry that the business models were changing - here was a white rapper on an independent record label with almost no radio presence having his debut at the top of the Billboard album chart. On this sometimes grueling album, the moments of lightness don’t come when Wale raps - guests like 2 Chainz and Meek Mill arrive like machetes cutting through thickets - but rather thanks to his ear for unexpected beats: the joyous soul of “Sunshine” the ecstatic gospel of “Golden Salvation (Jesus Piece)” and “Clappers,” featuring Juicy J and Nicki Minaj, which is inspired by go-go music (Wale is from Washington, that sound’s home, and he’s flirted with it over the years). Cole has used it as a reminder of the evils of bullying. And that makes it brave, in a way - rather than use his bully pulpit for evil, Mr. Cole, with heavy nods to the mid-1990s, though impressive in places, feels like an ideological relic. He would have been a hero in 1998.īut this album, largely produced by Mr. He’s not a disrupter by nature, only by circumstance.

Cole also suffers for arriving - waving outmoded treatises and arguments - into a hip-hop world that’s largely complacent with its success. Cole a force to be reckoned with on his early mixtapes. I got smart, I got rich, and I got bitches stillĪnd they all look like my eyebrows - thick as hellįor better and worse, these are the sorts of honest songs that made Mr. We ain’t picture perfect but we worth the picture still I keep my twisted grill just to show the kids it’s real He also has a song about not fixing his teeth just because he’s famous now, which takes a lemon and squeezes it hard: “Truth be told, I ain’t even bought a crib yet,” Mr.

He raps about all the money he doesn’t have, including a memorable line about Beyoncé telling him she wants to buy a Bugatti, and maybe realizing that car cost more than Mr. He has a song, “ Let Nas Down,” about letting Nas down. Cole ceaselessly invokes other rappers, both to place himself in their legacy and to show how far he has to go. Cole can be a fearsome rapper and a ponderous thinker, relentlessly tilling turf that Kanye West mastered and dispensed with a decade ago on his debut album. Cole and Wale have chosen one path, and Mr.

Now they’re hoping to demonstrate that they can remain stars. In 2011, they were trying to prove that the process of making hip-hop stars was changing. Cole and Wale, were signed to major labels, none of them made music that had much to do with the rest of major-label hip-hop.Īnd yet for a couple of months, new metrics like online penetration and ubiquity lined up neatly with old metrics like chart performance, reflecting the potency of those fan bases when given, in effect, an underdog to root for.Īll three rappers returned with new albums this month facing a different crossroads. All three had rabid fan bases, largely acquired online, where the mixtape circuit had migrated. These were not the old rap stars, but rather a new generation that represented a coming of age of the hip-hop Internet.

#WALE THE GIFTED BILLBOARD MAC#

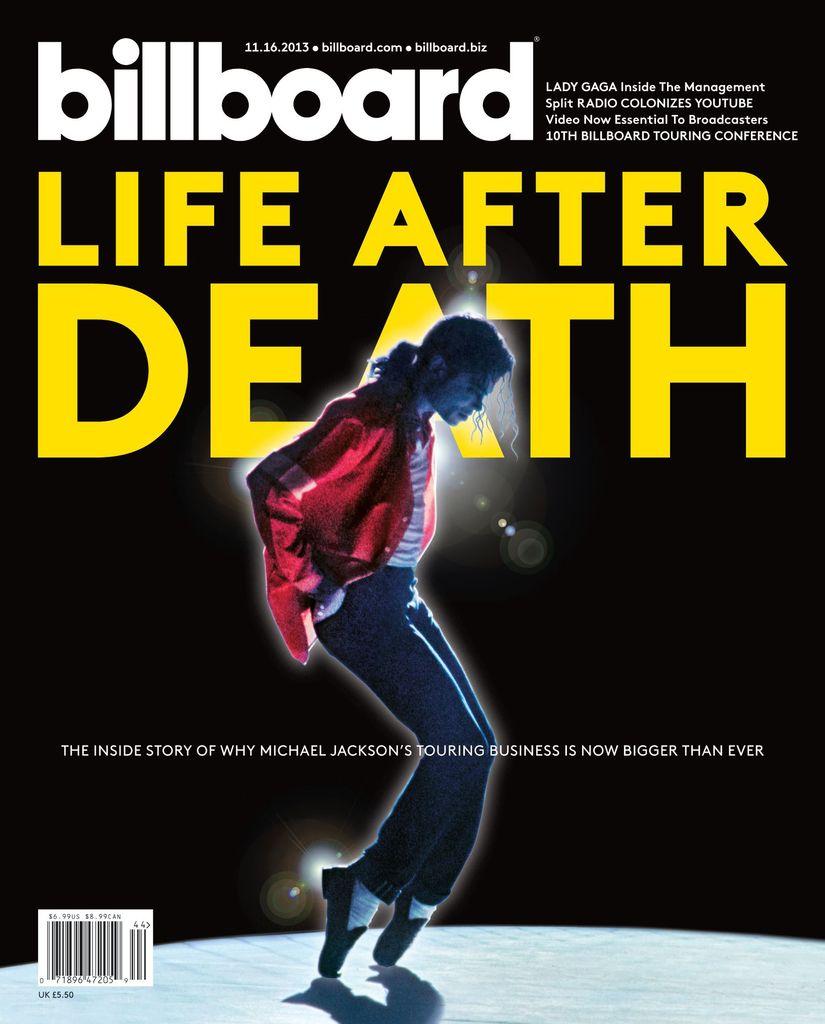

2, and not long after that, Mac Miller’s first album, “Blue Slide Park,” made its at No. A few weeks later, Wale’s “Ambition” (his second album) had its debut at No. Cole’s debut album “Cole World: The Sideline Story” made its debut atop the Billboard album chart and was certified gold. History rarely reveals itself in tight clusters of change, but for close watchers of hip-hop hierarchies, the end of 2011 must have been a confusing time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)